I recently posted on results from census data showing where we spend our time during the day. I also asked the question about your own views of time spent during the day. What would you prefer to do more of vs. what would you gladly have removed from your routine?

Better personal time use can cover letting go of unwanted activities and finding ways to automate (or outsource) repetitive tasks so that you can do something else that you enjoy more. My personal favorite example is the glimmer of hope from autonomous cars where we can potentially exchange the time focused on driving to more productive and fulfilling interests, letting the automated car perform the repetitive driving work.

'Doing more' also represents a potential need for augmentation causing us to ask deeper questions about what we would like to achieve from activities and which activities are most enjoyable.

The biggest bar on where the most time is spent in a day covers sleeping activity, typically eight hours a day. Many are tempted to dip into their sleep time in order to get more done in a day. Performing more activity during your waking hours at first seems like an easy trade-off yet we often are not able to measure the potential benefit of this trade-off vs. the cost.

With the topic of rationing down your sleep to do more, I took a look at the potential drawbacks with this strategy and perhaps how technology could assist us during potential impaired cognitive states.

Summary of health status and cognitive state vs. sleep loss with wearable detection

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration provides data which gives us a harsh reality of our inability to perform while driving. Conservative estimates show that 100,000 police-reported crashes are the direct result of driver fatigue each year. This results in an estimated 1,550 deaths, 71,000 injuries, and $12.5 billion in monetary losses. If you are not performing well enough to drive a car, imagine how poor you are performing making an important decision while fatigued?

Talk with any fatigued parent of a newborn and they will be very conscious of their impaired state of well being due to sleep loss. While we have the circumstantial and experiential evidence around us many continue to push their own mental and health limits for extended hours. Many also self-recognize problems that were difficult to solve while burning the midnight oil get solved easily the next day after a full nights rest. Sleep is very important in restoring serotonin and acetylcholine levels which are involved with a healthy operating memory as well as being involved with your ability to process experiences from waking hours.

Genetics give us information to base starting capabilities of what might be our optimal amount of rest (ADA gene makeup) and when we might perform the best during the day based on sleep (PER3 gene length). Combining this information with wearable based monitoring of sleep and health data and we can have active alerting on our mental and physical capabilities which would help us avoid situations that could cause us harm. This information can also be shared with others help them understand if an individual needs additional assistance.

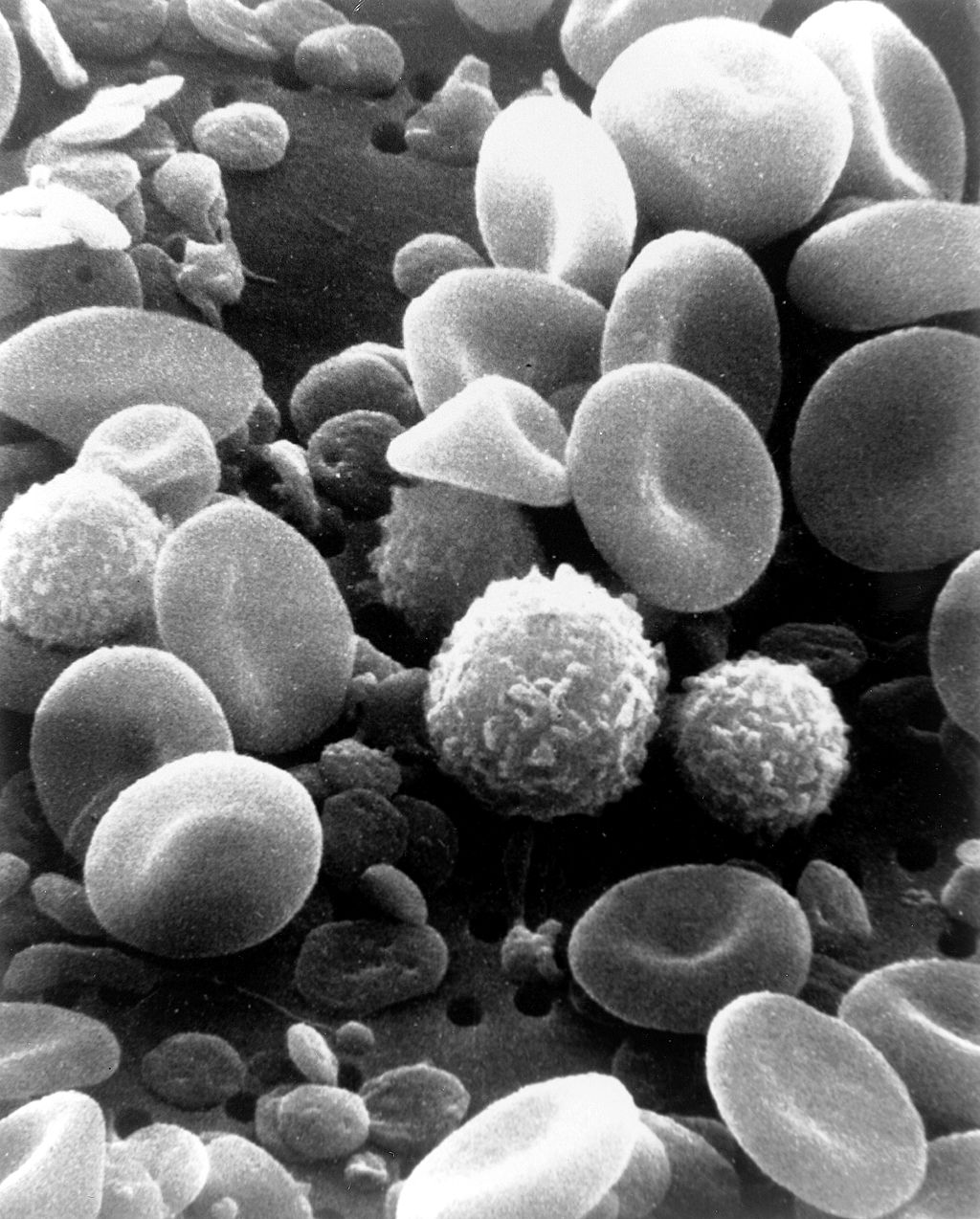

Our immune system also will show signs of impairment if sleep is not maintained to keep it functioning. To get this in perspective think of your immune system as an army waiting to defend you against virus, bacteria, parasite, and fungal invaders all the time. If you are not able to keep your immune system at an optimal state it will essentially start running out of ammo with evidence showing decreases in granulocytes / white blood cells, chronic inflammation, and inability to repair tissue damage. All of these lack of sleep symptoms have been attributed to many life-threatening health conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension.

During a time when we are tired or at a time when we have to trade our sleep for more activity there is a clear need for human augmentation to both assist us with our decisions while fatigued in addition to monitoring our state of well being. We are just starting to see the technologies needed to actively assist us with our self-understanding of health and cognitive state. Apps and wearables performing the monitoring functions will soon combine forces through collected data and machine learning algorithms to provide the personalized active feedback needed to keep, maintain and improve our health.

Resources:

- Paula Alhola, P. (2007). Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance. Neuropsychiatric Disease And Treatment,3(5), 553. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2656292/

- The Research Is Clear: Long Hours Backfire for People and for Companies. (2015). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2015/08/the-research-is-clear-long-hours-backfire-for-people-and-for-companies

- Sleep Deficit: The Performance Killer. (2006). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2006/10/sleep-deficit-the-performance-killer

- Ker, K., Edwards, P., Felix, L., Blackhall, K., & Roberts, I. (2010). Caffeine for the prevention of injuries and errors in shift workers. Cochrane Database Of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008508

- Immune system. (2016). Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immune_system

- Reference, G. (2016). ADA gene.Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/ADA

- (2016). Genecards.org. Retrieved from http://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=PER3

- A Length Polymorphism in the Circadian Clock Gene Per3 is Linked to Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome and Extreme Diurnal Preference : Epubs.surrey.ac.uk. Retrieved from http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/2847/5/Archer_Sleep_26_4.pdf

- Drowsy Driving. (2015). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/features/dsdrowsydriving/

- Facts and Stats : Drowsy Driving – Stay Alert, Arrive Alive. (2016).Drowsydriving.org. Retrieved from http://drowsydriving.org/about/facts-and-stats/

- Besedovsky, L., Lange, T., & Born, J. (2011). Sleep and immune function.Pflügers Archiv - European Journal Of Physiology, 463(1), 121-137. doi:10.1007/s00424-011-1044-0